Yesterday, data scientist Sarah Eaglesfield tweeted about some interesting facts she uncovered while looking into Wayne County, Michigan’s voter data from the November 2020 election. According to 100Percent Fed Up, her data, so far, explores cluster votes in Michigan’s Wayne County, where hundreds of affidavits have been filed sharing eye-witness accounts of voter fraud and intimidation by paid election workers and officials and Democrat activists present at the TCF Center, where absentee ballots were processed.

Eaglesfield’s tweet reads:

In order – clusters in Wayne County, Michigan with the most votes cast in #Election2020 were:

1. A psychiatric hospital (@NedStaebler is that you?)

This comment directed at Ned Staebler is in reference to his viral, videotaped, unhinged rant directed at the Republican Wayne Co. Board of Canvassers who refused to certify the county’s election last week.

2. Apartment block (but no apartment number)

3. A convent

4. THE FOUR SEASONS Care facility (really!)

5. Homeless drop-in centre

Today, Sarah Eaglesfield shared the data she used to obtain the information she shared on Twitter yesterday. She tagged Michigan’s Democrat Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson (who insists there was no voter fraud or intimidation of poll challengers in Wayne Co), Trump attorney Sidney Powell, President Trump, Joe Biden.

RE #1: The psychiatric hospital that, according to Eaglesfield’s research, provided the largest number of cluster votes in Wayne Co.

The largest cluster of votes received in Wayne County was from the Walter P. Reuther Psychiatric Hospital, which provides treatment, care, and services to adults with severe mental illness. 97 patients at the facility either applied for a ballot or are register as absentee voters, and 78 appeared to have returned their ballot.

From the Michigan.gov website: Walter P. Reuther Psychiatric Hospital provides treatment, care and services to adults with severe mental illness.

Given that the psychiatric facility in question specifically states that it caters to those with severe mental illness it should be investigated what mental capacity these voters had and whether these ballots were potentially abused. It is my understanding that there is no capacity test for voting in Michigan, although state law allows for one to be applied.

RE #2: Apartment block ( but no numbers)

The most striking thing about the Wayne Co. dataset in this regard is that there is no normalization of data in the Mailing Address field. This is a shortcoming in the software that could be abused for fraudulent purposes.

For example, some addresses have been written using the state abbreviation, and some with the full state name. Some have the house number contained in a separate field; some have it adjoined with the street name. In one case, the zip code field has been used to note that the address is an incorrect address.

The same issue exists in the residential address field, where there is no set format for apartment or studio numbers. Apartment numbers are sometimes stored with a “#”, sometimes as “Apt”, sometimes as “Apartment”, meaning that the same apartment number in the same block could be stored differently in the system, allowing voters to receive more than one voter number.

One example of a person with the same first name, middle name, address, and year of birth, who has been assigned different voter numbers, voted twice and been counted twice, has their address stored as both:

PIO BOX 32910 FORT ST POST OFFICE, DETROIT, MI 48323 and

PO BOX 32910, DETROIT, MI 48232-0910

Due to the shortcomings with regards to address format, it is difficult to provide a thorough analysis of voter clusters. An example of the problem can be seen, for example, in apartment blocks such as The Pavillion (1 Lafayette Plaisance St) where some residents did not even provide an apartment number.

RE #3: Convent

In the case of the Felician Sisters convent in Livonia, who sadly lost 13 of their sisters due to COVID-19 in May 2020, all their deceased had already been removed from the dataset.

Washington, MI Trump rally Nov. 1, 2020. Catholic nuns came out publicly in support of President Trump in Michigan and in other states, so it’s weird that the names of the deceased nuns were removed from the MI voter rolls, while names of dead voters across Michigan state remained on the voter rolls.

RE #4: The Four Seasons Care Facility

There are a large number of care centers catering for the elderly population within the county. Analysis found two instances where people had died in October, but their vote was still sent and counted. This isn’t problematic in itself, but there were a few care centers that stood out as suspicious – either through having returned all their ballots from the residents on the same day (Four Seasons Care) or through having received ballots for more than one deceased person who had previously been in their care (Hope Care).

RE #5: Homeless Drop-in Center

The State’s drive to allow homeless people to vote seems to have been successful, and there were a number of votes received from homeless drop-in centers and through the Samaritans. Although these cannot be verified, the numbers are consistent with what you would expect from a raised awareness campaign.

In addition to her findings related to cluster votes, Eagelsfield also released more evidence of voter irregularities that she discovered.

Wayne County Dataset

The Wayne County Dataset was obtained from Jocelyn Benson, the Secretary of State for Michigan. It contains 613,091 lines of data, each representing a vote cast in Wayne County, including voters’ personal information (such as name, home address and year of birth). It is a partial dataset and does not contain all the voter data for Wayne County.

Forensic Analysis Questions

There are a number of questions that can be asked to help determine the integrity of the election data provided. Although one factor on its own would not point to election fraud having taken place, these questions can still help determine shortcomings in the computer systems used to process the ballots, and where human error may have occurred.

Q1. Is rejection rate in line with other years?

If the rejection rate was significantly higher than other years, this would indicate a possibility that valid ballots were being rejected. Conversely, if the rejection rate was significantly lower, it would point to potentially legal ballots being disregarded.

A1.

7,700 votes were rejected in the provided dataset, a rate of 1.256%. This is lower than the statewide 2016 Michigan rejection rate of 2.02% stated by the Election Assistance Committee in their 2016 Election Administration and Voting Survey. Although not an immediate cause for concern, given the increase in absentee ballots, rejection rates would be expected to be higher than previous elections, and ballot rejection procedures should be reviewed in the audit.

Q2. Does any voter ID appear more than once in the dataset?

As each voter ID represents a unique person, and each person is only allowed to vote once, a voter ID appearing more than once should be flagged as suspicious.

A2.

A total of 1,104 voter IDs appeared more than once in the dataset, with 4 voter IDs appearing three times, and one voter ID appearing four times.

Whilst the majority of duplicate voter IDs were processed correctly, the dataset appears to show 21 processing errors with these duplicates. 10 voters with the same voter ID who voted twice appear to have been counted twice, two of whom had changed their address, one of whom was an overseas voter. 5 voters voted twice and had neither vote counted. 6 voters had their ballot counted more than once, as detailed below.

Q3. Does any ballot ID appear more than once in the dataset?

As each ballot ID represents a unique vote, a ballot ID appearing more than once should be flagged as suspicious.

A3.

A total of six ballots were counted more than once according to the provided dataset. Of these six, four were counted twice, one was counted three times, and one was counted four times.

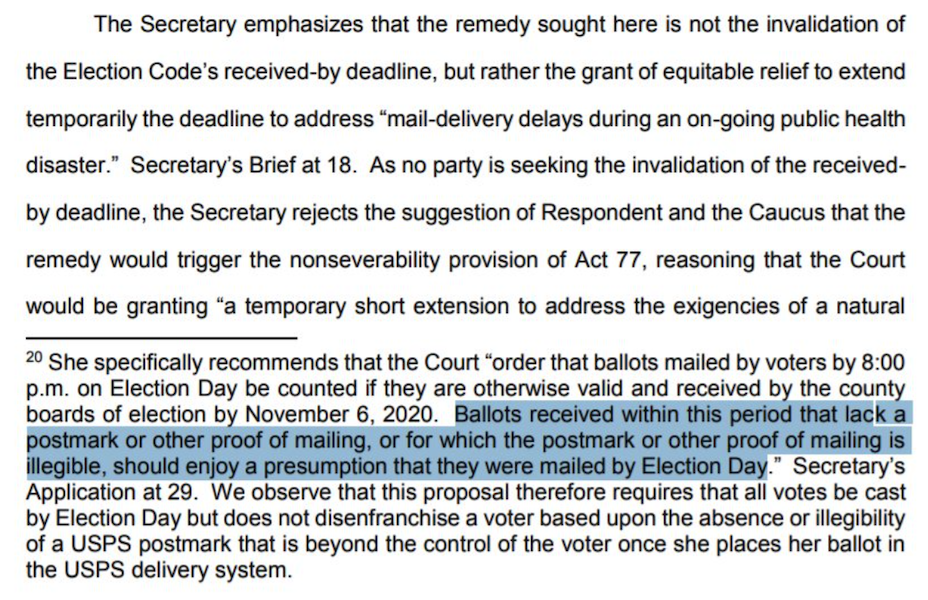

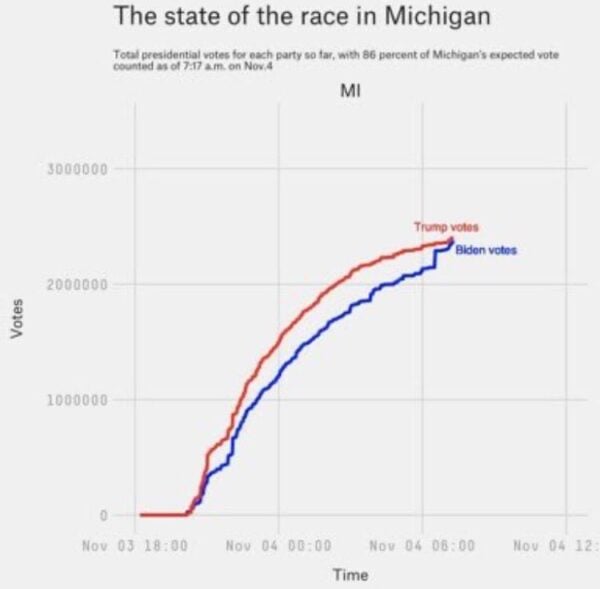

Q4. Were ballots received after the cut-off date rejected?

The Michigan Court of Appeals ruled that voters in Michigan must return absentee ballots to their clerk by 8 p.m. on Election Day (November 3rd) in order for their vote to count. Were any votes received after this date processed?

A4.

13 ballots are shown to have been received on 4th November, of which 11 were rejected and 2 were accepted.

It is possible that the dataset provided could have been generated using UTC, which is 5 hours ahead of Michigan Eastern Daylight Time, and this may account for the two late ballots being accepted. However, there is no exact timestamp given, and considering there is evidence that some ballots received on the 4th of November may have been processed, it is also possible that other votes were counted which arrived after 8 p.m. EDT on November 3rd, 2020.

By

By

Political cartoon by A.F. Branco ©2020.

Political cartoon by A.F. Branco ©2020. Political cartoon by A.F. Branco ©2020.

Political cartoon by A.F. Branco ©2020. Political cartoon by A.F. Branco ©2020.

Political cartoon by A.F. Branco ©2020.

Reported by

Reported by

Lieutenant Jeff Neville, who was bleeding from the neck, sources and witnesses at Bishop International Airport said.

Lieutenant Jeff Neville, who was bleeding from the neck, sources and witnesses at Bishop International Airport said.

Several politicians have recently been offering free goodies to voters. One of the most popular of these, oddly enough, is something that several state governments have already tackled: free college tuition.

The details vary by state, but Oregon, Tennessee, Georgia, Michigan, and Louisiana (among others) all use tax dollars to pay for at least some of their residents’ college tuition.

Louisiana provides a great case study for advocates of similar federal policies. Louisiana just so happens to be in the news right now because the governor is threatening to suspend his state’s version of free college tuition for everyone.

Louisiana’s Tuition Program

Louisiana’s plan is called the Taylor Opportunity Program for Students, or, more commonly, TOPS. This extremely popular program uses tax dollars to pay full tuition (and some fees) at any of Louisiana’s public universities. Other than residency requirements, all high school students qualify as long as they have a C average (2.5 GPA) and at least an 18 on the ACT.

So the Taylor Opportunity Program for Students doesn’t cover every student’s tuition, but it ends up covering it for a large chunk of middle-/upper-class families.

How It Started

The program started out in the late 1980s as the brainchild of oil tycoon/philanthropist Patrick Taylor. The program, which wasn’t originally named for him, started out as a tuition assistance plan only for low-income individuals.

In 1997 the state removed the income caps. At that point, all Louisiana students, regardless of financial need, were made eligible for “free” tuition at any Louisiana public college. Once in college, students had to maintain a C average to keep their TOPS awards.

As of 2010, approximately 70 percent of Louisiana’s high school graduates headed to college within one year. That’s nearly 20 percent higher than the rate in 2000.

Who’s Paying for It?

It’s easy to call the program a success because of this increase, but it’s just as easy to point out that the program doesn’t really provide free education. In one way or another, someone pays for it.

The eventual implosion of the program was easy to predict back in 1997 for the same reasons that pretty much any similar subsidy is destined to fail. Subsidies don’t really lower the cost of products and services; they only lower the up-front price that some people pay.

(In 1997, this program inspired my very first public critique of a government policy. Back then, I thought it was a terrible idea.)

No Such Thing as Free Tuition

A person receiving “free” tuition may not see it (or even care), but subsides actually raise the total cost of an education. The core problem is that they remove the paying customer—in this case the student—from the equation.

Without the subsidy, the paying customer receives the direct benefit for the service and bears the direct cost. If that person doesn’t think the cost is worth it, they don’t pay.

Louisiana’s program replaces this paying customer with groups of government officials. These officials neither receive the direct benefit nor endure the direct cost of obtaining an education. These groups do, however, benefit a great deal from obtaining more of your tax dollars.

And they rarely bear any direct cost from either increasing your taxes or delivering a substandard education product. (The incumbency rate is fairly high for politicians.)

On a practical level, Louisiana’s program converts tuition payments into a state budget item. In other words, a large chunk of each school’s “tuition” becomes nothing more than revenue sent in by the state bureaucracy.

In Louisiana, four separate higher education systems—each its own bureaucracy—fight over these “tuition” payments. Smaller schools inevitably get the smallest shares, but that’s kind of another story.

A Burden on University Resources

When the influx of students hits—more people going to school when tuition is “free” is pretty much a foregone conclusion—it strains universities’ existing resources. So the transfer of money has the natural tendency to lead to expanded facilities, faculty, and staff.

But these increases call for a permanently higher level of funding, and all of these effects tend to reinforce each other. That is, school officials have a built in reason to ask for larger transfers, and politicians have a built in excuse to raise taxes.

When the state’s coffers are not flush with cash, the schools’ budgets get cut. Thus, universities have every incentive to raise more money from students who are not a part of the Taylor Opportunity Program.

Of course, for any given level of Taylor Opportunity Program students, a higher posted rate of tuition results in a larger transfer from the state. If the program covered full fees and tuition for literally every student, then taxpayers would bear the full cost. But it doesn’t, so non-TOPS students bear some of the cost.

(Pretty much every student ends up paying higher fees directly, too, but that’s almost an aside.)

Non-subsidized markets don’t work this way—prices can actually fall in response to changes in demand and supply. Subsidized systems, on the other hand, are destined to result in higher—not lower—tuition.

Recent numbers support this explanation. The Taylor Opportunity Program has nearly doubled in cost since 2008, and most of that increase has been due to higher tuition.

What I failed to fully appreciate in 1997 was how bad of a deal the Taylor Opportunity Program would end up being for the smaller schools. Then I spent almost a decade teaching at Nicholls State University, a regional state school in Thibodaux, La.

Small Universities Are Hardest Hit

In one sense, the Louisiana program amounted to a cruel trick for these institutions. Smaller schools are the ones least able to sustain the permanently higher costs associated with the new TOPS-generated revenue stream.

When the state budget goes south—and it always does in Louisiana—smaller schools get slammed. (Louisiana State University has more than 25,000 students, so small changes in per-student fees go a long way).

No matter how much we want it to, subsidizing something simply doesn’t make it more cost-effective.

The Taylor Opportunity Program does give certain people a better deal on tuition at one point in time, but then it makes up for it somewhere else.

Ironically, the earlier waves of Taylor Opportunity Program graduates are among those about to get hit with a tax increase. That’s what politicians mean by free.

Aside from the subsidy/cost issue, there are many other reasons why this is bad public policy.

First of all—and I know this sounds crazy—everyone should not go to college. Some people simply aren’t cut out, and many just don’t need to. Yes, people with college degrees tend to earn more than those without, but it does not follow that everyone should go to college.

When the program was started, Louisiana public universities offered students a good value because they were relatively inexpensive. Now that Louisiana taxpayers have spent more than $2 billion on the program, tuition rates are out of reach for many students that don’t qualify for the program.

While the best solution for Louisiana would be to get rid of the program altogether (unlikely since politicians love the program), the best residents can hope for now is an increase in the program’s academic standards and some form of means testing. At least these changes would better direct subsidies to academically prepared students with more financial need.